The Art and Practice of Wild-Tending

By Mandana Boushee

My family, like many Iranians, left Iran after the Iranian Revolution of 1979, first traveling to Greece, then England, and finally settling in the Hudson Valley of New York. Upon arrival in New York, my mother was distraught that so many of Iran’s celebrated ingredients could not be found at U.S. markets and grocery stores. Commonly eaten dishes were now impossible to make, as so many herbs, fruits, and vegetables are unique to Iran.

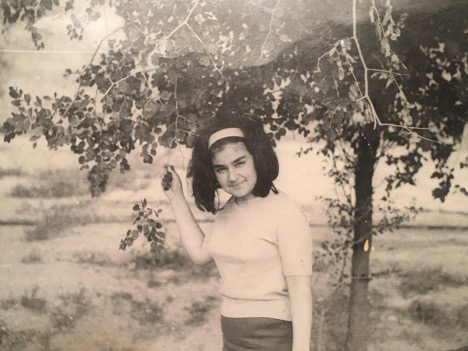

In Iran, wildcrafting is a very common pastime and tradition. Even in the busy capital of Tehran, thousands will head out of the city in the summer to picnic and enjoy the start of the black mulberry (Morus nigra) harvest. My mother spent her childhood frolicking in her mother’s gardens, fishing in the stream with her father, and as a family foraging from the wild.

As my mother began settling into her newly foreign life, still living within the heartbreak of diaspora, she slowly began to remember herself. She soon began to recognize familiar plants growing in New York. Though slightly different than the species growing back home, she found comfort in the family resemblance. Soon, plants like barberry, sumac, mulberry, mimosa, and sour cherry were finding their way back into the kitchen of our souls.

My mother foraging in Iran

So, I can’t recall the first time I went foraging with my mother, but I do remember the first time I realized that wildcrafting wasn’t something the average American did. I was about seven years old when my mother and I were collecting sour cherries from our next door neighbor’s tree. My mother had a way of befriending all of our neighbors, and eventually had been granted permission to harvest from neighbors’ gardens that went unpicked.

A passerby stopped to ask what we were doing, as my mother excitedly explained that we were harvesting the fruit. Shocked, he shook his head, told us we could get poisoned, and walked away. I remember feeling a deep sense of embarrassment and shame. Life wasn’t easy for us, and I knew as a young girl that our way of life was very different than a lot of my neighbors and classmates.

Sometime after this encounter, I stopped going on foraging walks with my mother and for a time, I hid from my rituals and customs. Luckily over time, a rose in bloom can remind us of the spectacular miracle that is the living world around us. It wasn’t long after that, that I was reignited by the macrocosm of plants.

Reconsidering Wild-Crafting

By 18, I was backpacking around the world and U.S., self-studying plants, herbalism, and learning to subsist more than ever on a wild food diet. I felt pride to be practicing my traditions as my relatives did before me, while also carrying a new sense of agency in having access to self-reliant strategies and food economies.

When I finally settled back in the Hudson Valley in my late twenties, our country was beginning to wake from a long slumber. People were questioning, challenging, and examining our relationships to land, food, and health. Soon restaurants began introducing wild foods onto menus, successfully igniting a desire and excitement in trying new flavors and ingredients. That growing excitement also manifested in the health and medicine industries, and eventually into the beauty economy. Medicines like bitters, chaga, and elderberry were becoming common in mainstream culture.

It was during this time that I began to see changes in the woods and lands I’d known and loved since childhood. The first sign of disrespect and misharvest I discovered was with the ramps that grew in one of my most beloved hollows.

In this undisturbed forest, many native plants grew in abundance. Spring beauties, toothwort, and red trillium carpeted the spring forest floor but none more than the ramps. Up on a steep ridge laid acres of tightly packed ramps. In my years walking the land, I learned from the elders who still foraged in these forests that they waited until the late spring to harvest the ramps, when the bulbs were the tastiest and juiciest.

Each late spring, I’d climb the ridge in search of clumps of tightly packed ramps. Loosening the soil, from clusters of three, I’d harvest the middle-sized bulb, making sure to leave the root behind. Before covering the remaining bulbs back in the dirt, I’d give each bulb a little more room to grow before packing the dirt in and around them. Though it was time consuming, I gave thanks to each plant I disturbed and harvested, and by the end of the day, I’d leave with a beautiful bundle of ramps and a deep sense of gratitude.

Each late spring, I’d climb the ridge in search of clumps of tightly packed ramps. Loosening the soil, from clusters of three, I’d harvest the middle-sized bulb, making sure to leave the root behind. Before covering the remaining bulbs back in the dirt, I’d give each bulb a little more room to grow before packing the dirt in and around them. Though it was time consuming, I gave thanks to each plant I disturbed and harvested, and by the end of the day, I’d leave with a beautiful bundle of ramps and a deep sense of gratitude.

So I was troubled one spring, when along the trail to the ridge, I found a ramp unearthed with its roots still intact on the trail floor. As I looked up, I quickly noticed a trail of ramps leading to the ridge. Slowly I began to realize that someone must have harvested the ramps, and carelessly didn’t bother to pick up any that fell on their way out of the forest. Once I’d made my way to the ridge, I was shocked to find the state the land was left. Whoever had harvested the ramps hadn’t even bothered to climb the ridge, taking the closest and first ramps that grew, leaving not a single behind. I was sick to my stomach, and sat awhile, feeling through so many emotions. I didn’t harvest any ramps that day.

When I got back home, I was overwhelmed with a sense of loss. A practice I loved, felt culturally attached to, and that was connected to my sustenance, was in danger. Though I practiced ethical wildcrafting, I knew I couldn’t continue harvesting ramps from that hollow anymore.

At that time, I’d often take time when walking in the woods to pick up trash or pull out garlic mustard plants that were finding their way into native plant habitats. When I’d hear word of land being deforested, a group of friends and I would rescue whatever plants we could, before the dirt was covered with blacktop. These acts felt important to me, as a way to reciprocate the gifts I received from the plants, but that day with the ramps brought important truths and lessons to light.

The Art and Practice of Wild-Tending

Though I felt connected to nature, and in good relationship, I too assumed that I had an unspoken permission to harvest. I realized it didn’t matter if I thought I was harvesting ethically. Questions that kept coming up for me were, was my relationship to plants healthy and generous? Was I responsibly engaging in relationship? What were other ways I could connect with wild plants? The more I listened and questioned, the more I learned that there were a multitude of ways to engage with plants in the wild.

For me, I call this practice and relationship in my own life, wild-tending. I’ve re-centered practices that feel regenerative and give me more opportunities to build language and friendship with plants, like crafting flower, plant, and environmental essences or sitting with plants and deeply listening. I tend plants in the wild, supporting the many different forms of plant reproduction.

In return, I receive the gift of joy felt throwing wish-filled milkweed seeds to the wind to disperse. I have become a better scavenger, taking what the wind and rain leave behind. I am grateful for the resilient, abundant, adaptive plants that some call invasive. I feed the soil nourishing teas, whispering prayers to all of its mysterious moving parts. I am astounded by all the ways the land gives, and I let it rest, not expecting it to always be productive or of use. I am fed in a new way, the harvest now takes many forms and is full of lessons.

As herbalists, land stewards, and plant admirers, we are being asked to question our relationship to the land and natural resources. It feels now more than ever that the land is asking us to give it more care and dedication. We are being called to do more, to activate, to speak up and out. As we begin to reflect wild-tending into our practices, schools, businesses, and apothecaries, we are discovering the tiny tears that were there hiding all along. Injustice, greed, and disrespect of the land has brought us onto the shores of our new shared reality. We are facing an angry earth, and the long grief that comes with the loss of our home.

It is time for us to remember the bird call, the fruit that brings us to tickle the trees, the feel of moving water on our hands. We have the opportunity to unconditionally bring the reishi mushroom and hemlock tree a feast of food for its saprobic relationship, the river water a shiny stone for its life-giving qualities, and the mountains a song to echo for its strength and stability. May we find ways to tend this wild seed we live, into a bouquet of beautiful creation.

![]() Mandana Boushee is an Iranian-American herbalist, writer, gardener, and educator at Wild Gather: Hudson Valley School of Herbal Studies. She weaves her Iranian lineage, ancestry, and plant tradition into all facets of her work as an herbalist. As a woman of color, she is dedicated to re-centering the voices, stories, rituals, and histories of the BIPOC community, particularly around health, healing and food.

Mandana Boushee is an Iranian-American herbalist, writer, gardener, and educator at Wild Gather: Hudson Valley School of Herbal Studies. She weaves her Iranian lineage, ancestry, and plant tradition into all facets of her work as an herbalist. As a woman of color, she is dedicated to re-centering the voices, stories, rituals, and histories of the BIPOC community, particularly around health, healing and food.